Conference Themes

- Literature and poetry

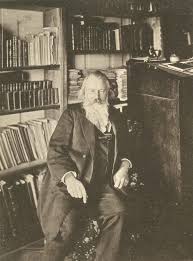

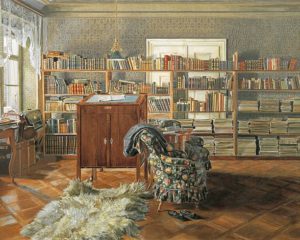

The music of Brahms is intricately linked to the German intellectual tradition. Within his song output alone, Brahms set 46 poets, including respected names such as Goethe, Eichendorff, and Heine, and many lesser known poets. Brahms also set many literary and philosophically-based texts by writers such as Goethe, Schiller, and Hölderlin in his choral works. His treatment of the Luther Bible as a piece  of German literature is found in some of his most renowned works such as Ein deutsches Requiem and the Vier ernste Gesänge. Whereas the majority of the poets Brahms set were German, the imaginative realm of that poetry reaches far beyond German borders, extending, for example, to China in his setting of Goethe’s Chinesisch-deutsche Jahres- und Tageszeiten, to Persia in his settings of Daumer’s Hafis poetry, and it conjures up ancient Greece in his Sapphische Ode and other works. Equally broad is the chronological reach of his literary interests, extending from classical antiquity through Medieval Europe, and on to the nineteenth century. This conference will explore the poetic and literary aspects of Brahms’s compositional output drawing on evidence from the composer’s library, sketches and manuscripts, and correspondence. In relation to theme 3 below, it will also consider the work of recent composers, for example Wolfgang Rihm, who have returned to the literature Brahms set, by way of paying homage to or even “recomposing” Brahms in works such as Symphonie “Nähe Fern” (2012). The focus on Brahms and literature will also prompt discussion of the presence of Brahms in literary fiction by authors such as Thomas Mann, E. M. Forster, and Milan Kundera.

of German literature is found in some of his most renowned works such as Ein deutsches Requiem and the Vier ernste Gesänge. Whereas the majority of the poets Brahms set were German, the imaginative realm of that poetry reaches far beyond German borders, extending, for example, to China in his setting of Goethe’s Chinesisch-deutsche Jahres- und Tageszeiten, to Persia in his settings of Daumer’s Hafis poetry, and it conjures up ancient Greece in his Sapphische Ode and other works. Equally broad is the chronological reach of his literary interests, extending from classical antiquity through Medieval Europe, and on to the nineteenth century. This conference will explore the poetic and literary aspects of Brahms’s compositional output drawing on evidence from the composer’s library, sketches and manuscripts, and correspondence. In relation to theme 3 below, it will also consider the work of recent composers, for example Wolfgang Rihm, who have returned to the literature Brahms set, by way of paying homage to or even “recomposing” Brahms in works such as Symphonie “Nähe Fern” (2012). The focus on Brahms and literature will also prompt discussion of the presence of Brahms in literary fiction by authors such as Thomas Mann, E. M. Forster, and Milan Kundera.

- Philosophy and critical theory

Brahms’s broad intellectual curiosity was often concerned with philosophical issues. From an early age and throughout his life he read widely and kept a log of proverbs and philosophical sayings that were significant to him. His library testifies to an enduring interest in philosophical matters. Along with the volumes of Herder, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche that he read and annotated were anthologies of philosophy such as Friederike Kempner’s volumes, the first of which (1883) contains excerpts of Kant, Locke, Cartesius, Friedrich the Great, Marcus Aurelius, and Rousseau, and the second (1886), passages from Plato, Leibniz, Wolf, Cicero, amongst others. Brahms drew much of his philosophy from literature, the Bible being a prime example. In his setting of secular texts, he sought out the same difficult questions as in his secular works in order to “legitimize” them. Yet his philosophical interests were by no means limited to these areas.

Brahms’s broad intellectual curiosity was often concerned with philosophical issues. From an early age and throughout his life he read widely and kept a log of proverbs and philosophical sayings that were significant to him. His library testifies to an enduring interest in philosophical matters. Along with the volumes of Herder, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche that he read and annotated were anthologies of philosophy such as Friederike Kempner’s volumes, the first of which (1883) contains excerpts of Kant, Locke, Cartesius, Friedrich the Great, Marcus Aurelius, and Rousseau, and the second (1886), passages from Plato, Leibniz, Wolf, Cicero, amongst others. Brahms drew much of his philosophy from literature, the Bible being a prime example. In his setting of secular texts, he sought out the same difficult questions as in his secular works in order to “legitimize” them. Yet his philosophical interests were by no means limited to these areas.

Both in his lifetime and following Brahms’s death, the writings of musical figures such as Heinrich Schenker, Hugo Riemann, Ernst Kurth, and of cultural figures such as Friedrich Nietzsche, Theodor Adorno and Ernst Bloch have influenced how we have come to see and understand Brahms in the fields of music theory, music analysis, and critical theory. Tracing the different lineages of these figures helps us to understand how Brahms and Modernism interacted in the twentieth century. This conference will explore the nature, range, and scope of Modernism as a movement in relation to Brahms. It will explore the extent to which Marxist theory exerted an influence on judgments of taste in Brahms’s music. It will further widen its scope to consider how music analysis and critical theory interact in Lacanian, Badiouian, and Žižekian readings of Brahms.

- Brahms’s compositions and recomposing Brahms

The sphere of Brahms’s intellectual world continues to widen as composers from the 1970s to the  present compose pieces that respond directly to the music of Brahms in conceptually fascinating and multifaceted ways. These composers come from within and beyond the German-speaking realm, ranging from the Hungarian composer György Ligeti (1923–2006) to the British composer Thomas Adès (1971–) and the American composer Missy Mazzoli (1980–). There are those who wish to expand on Brahms’s musical thinking, such as Detlev Glanert (1960–); those who engage with Brahms by way of offering critical reflection upon the role of history such as Michael Finnissy (1946–); those who respond to Brahms by way of pointed critique, such as Adès; those who attempt to recompose the “particles” of Brahms’s music as though Brahms himself had not first composed his own pieces, such as Wolfgang Rihm (1952–). There are also composers who respond to the same literature as Brahms, aiming to reconceptualize not only Brahms’s music, but also these literary and poetic works. The broad theme of “recomposing Brahms” has many fascinating intersections with critical theory, as outlined in the theme 2 above.

present compose pieces that respond directly to the music of Brahms in conceptually fascinating and multifaceted ways. These composers come from within and beyond the German-speaking realm, ranging from the Hungarian composer György Ligeti (1923–2006) to the British composer Thomas Adès (1971–) and the American composer Missy Mazzoli (1980–). There are those who wish to expand on Brahms’s musical thinking, such as Detlev Glanert (1960–); those who engage with Brahms by way of offering critical reflection upon the role of history such as Michael Finnissy (1946–); those who respond to Brahms by way of pointed critique, such as Adès; those who attempt to recompose the “particles” of Brahms’s music as though Brahms himself had not first composed his own pieces, such as Wolfgang Rihm (1952–). There are also composers who respond to the same literature as Brahms, aiming to reconceptualize not only Brahms’s music, but also these literary and poetic works. The broad theme of “recomposing Brahms” has many fascinating intersections with critical theory, as outlined in the theme 2 above.

- History, race, and identity politics

Brahms had a keen interest in German political history, counting the writings of seminal figures such as Heinrich von Sybel and Heinrich von Treitschke among the volumes in his library. His compositional output engages in meaningful and tangible ways with political events in German-speaking Europe from the time of Napoleon to the formation of a German nation-state in 1871. Brahms strongly identified with the Lutheran heritage of his boyhood and youth and maintained his cultural Protestantism despite losing his faith in adulthood. This informs his compositional output in manifold ways, from the presence of Lutheran chorales in a broad range of his instrumental works, to the composition of more overtly political and patriotic works such as the Triumphlied, and Fest- und Gedenksprüche, whose texts he culled from the Luther Bible.

Brahms’s output has been considered at various times in relation to different issues of race and ethnicity. Between 1898 and 1938, a number of books and articles were published that suggested that Brahms may have had a Jewish heritage. This rumor played into the reception of the composer’s music during the era of National Socialism. More recently, researchers have challenged the notion that Brahms’s music is free from race politics, exploring performances of his works within the German realm by the black diaspora from the 1870s onward. This research poses important questions about whether audiences during Brahms’s lifetime responded to performances along racial lines. Questions concerning the politics and aesthetics of musical performance in the second half of the nineteenth century open onto wider debates on contemporary issues regarding the question of whether “Western art music”—a concept that, in itself, has been broadly problematized—is a repertoire that is free from race politics or gender politics. Through exploring these topics, the conference also questions what relevance a white, European, nineteenth-century composer can have in the United States today. This conference aims to provide a space for the broad and open discussion of these issues.

Brahms’s output has been considered at various times in relation to different issues of race and ethnicity. Between 1898 and 1938, a number of books and articles were published that suggested that Brahms may have had a Jewish heritage. This rumor played into the reception of the composer’s music during the era of National Socialism. More recently, researchers have challenged the notion that Brahms’s music is free from race politics, exploring performances of his works within the German realm by the black diaspora from the 1870s onward. This research poses important questions about whether audiences during Brahms’s lifetime responded to performances along racial lines. Questions concerning the politics and aesthetics of musical performance in the second half of the nineteenth century open onto wider debates on contemporary issues regarding the question of whether “Western art music”—a concept that, in itself, has been broadly problematized—is a repertoire that is free from race politics or gender politics. Through exploring these topics, the conference also questions what relevance a white, European, nineteenth-century composer can have in the United States today. This conference aims to provide a space for the broad and open discussion of these issues.

- Brahms on the Pacific

Although Brahms himself never set foot in the United States, a number of intellectual figures within his intellectual orbit were amongst the exiles from Nazi Germany who took up residence in Los Angeles. These include Arnold Schoenberg, Thomas Mann, and Theodor Adorno, each of whom is also independently related to the conference themes outlined above. The conference will consider the relationship between Brahms and these German exiles, thereby situating Brahms within an important era of Californian history.